Superfluous variants in the readings of the Qurʼān

Previous article: Dialogue variants in the canonical Qirāʾāt readings of the Qurʼān

This article looks at another class of canonical variants at the other end of the spectrum. One thing I found very noticable while looking through variants for the earlier work was the large number that do not convey any additional meaning (though exegetes sometimes try). Human poets may typically vary their recitations in such ways, though they also bring with them the usual cost of looking like human errors or changes creeping into the transmission. These are some of the common categories.

- Plural-singular variants

A few examples are given below.

21:104 The Kufan readers (except Šuʿba’s transmission of ʿĀṣim) here read li-l-kutubi (for the books), as indeed did ibn Masʿūd, reportedly. The others read li-l-kitābi (for the book). The same readers who use kitāb singular here readily use kutub plural in other verses.

Corpus Coranicum Tafsīr al-Jalālayn (they give interpretations of the verse, but none that explain any value of the variant).

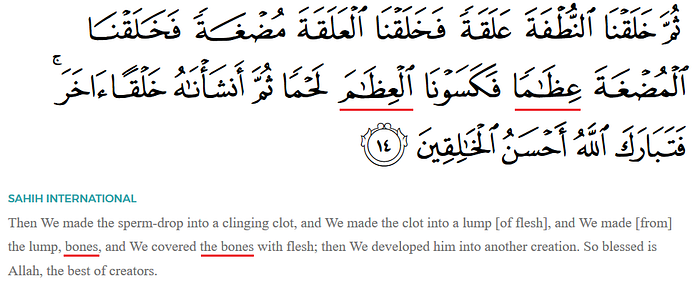

23:14 Abū ʿAmr and Šuʿba’s transmission of ʿĀṣim twice read here ʿaẓman (bone, meaning bones collectively) while the others read ʿiẓāman (bones). All readers have no problem reading the plural in 2:259.

Corpus Coranicum Tafsīr al-Jalālayn

59:14 Ibn Kaṯīr and Abū ʿAmr read ǧidārin (a wall singular), whereas the others read ǧudurin (walls plural). There is no reason to have both.

Corpus Coranicum Tafsīr al-Jalālayn

2. Active-passive

This kind of variant is also common, very often adding no additional meaning. Here are some typical examples:

4:124 Ibn Kaṯīr, Abū ʿAmr, and Šuʿba’s transmission of ʿĀṣim read yudḫalūna (those will be entered), while the others read yadḫalūna (those will enter). The former already implies the latter, so why recite both?

Corpus Coranicum Tafsīr al-Jalālayn

4:140 ʿĀṣim reads nazzala (It has come down), while the others read nuzzila (it has been sent down). The active is already implied by the passive.

Corpus Coranicum Tafsīr al-Jalālayn

23.115 Ḥamza and al-Kisāʾī read tarǧiʿūna (return), while the others read turǧaʿūna (be returned).

Corpus Coranicum Tafsīr al-Jalālayn

3. More-less intensive verb form

Also commonly, the more intensive/causitive verb form II is used, with a meaning that already implies the form I reading. One example will suffice:

21.96 Ibn ʿĀmir reads futtiḥat (has been opened wide; Arabic verb form II), whereas the others read futiḥat (has been opened). The first reading already implies the other. The same variants appear in different reader permutations in other verses in the context of gates opening (39:71 and 73, and 78:19).

Corpus Coranicum Tafsīr al-Jalālayn

4. Qul-Qāla

There are several verses where we have the variant reading qāla (He said) instead of qul (Say). There is no additional information from the qāla variant because it already follows from his recitation of the qul variant that, in so doing, “he said” it. One example will suffice:

72:20 ʿĀṣim and Ḥamza read qul, whereas the others read qāla.

Corpus Coranicum (No comment on the variant in Tafsīr al-Jalālayn)

5. Wa, fa

The word wa (and) is sometimes added or omitted for no apparent reason, or instead is read as fa (and then) as in 91:15 (wa and fa are indistinguishable in the rasm without consonantal dots). An example of the former is:

2:116 Ibn ʿĀmir reads qālū (They say) whereas the others readers have wa qālū (And they say). Like the other types of variants in this article, we could well ask why we have the variance in some places but not others if they are not transmission errors.

Corpus Coranicum Tafsīr al-Jalālayn

Like some instances of Qul-Qala, some of these were regional variants (or scribal errors) in the Uthmanic rasm (consonantal skeleton).

Incidentally, any supposed deliberate purpose of these variants existing in the variant Uthmanic codices encounters a difficulty. Canonical readings supposedly must comply with the Uthmanic rasm or the regional variants thereof, yet at the same time the canonical readings were allowed to transgress them sometimes anyway (such as 19:19 mentioned in my first article).

6. Variants overkill

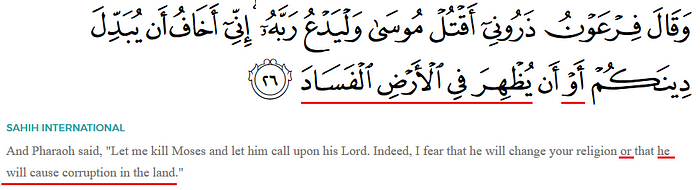

40:26 The canonical readers give a total of four permutations of Pharaoh’s words here, both on whether he said ʾau ʾan (or that) or wa-ʾan (and that) and on whether he said yuẓhira fi l-ʾarḍi l-fasāda (he will cause corruption in the land) or yaẓhara fi l-ʾarḍi l-fasādu (corruption may appear in the land).

Corpus Coranicum Tafsīr al-Jalālayn

A similar example occurs in Q19:25 where in the sentence “And shake toward you the trunk of the palm tree; it will drop upon you ripe, fresh dates”, Yaʿqūb reads “it” meaning the trunk, while the other readings have three other forms of the word where “it” refers to the palm tree, with or without consonant doubling to emphasise a great dropping of dates. Why this strange overkill, not to mention several further non-canonical variants? (see Corpus Coranicum). What would be the point in deliberately reciting so many variants in such sentences?

Some theological questions that spring to mind

Though the Qurʼān itself (3:7) famously suggests that some verses are unclear / allegorical, it doesn’t mention the existence of reading variants. While the meaning is usually clear in each of these pairs of variants in this article, any benefit or reason to have both of them is not. What would be their divine purpose? These superflous variants fit right into the general pattern of variants that look like they arose during transmission.

Similarly, why does each category arise only in certain places and not others? The same could be said for some other variants that do slightly change meaning, where in some places you have the pair of variants and others just one of them. This again naturally looks like changes arising unintentionally during transmission, or a sometimes loose approach to recitation by the Prophet.

Exegetes sometimes strive to layer on some meaning in these kinds of variances, yet no real difference is apparent from the Qurʼān itself. If there are canonical variants that bring no or negligible additional meaning, and at the same time come at the cost of looking very plausibly like human error or indifference, it is especially straightforward to explain them as being so, whether they arose from the Prophet or later transmission.